Postponed from last week, new date is January 13th. I don’t suppose any of my subterranean historic degenerate friends will be there.

SLIders: Street Light Interference…

I remember when I was working for law firms in downtown DC. This had to be in the 1990s. I was leaving work in the dark or semi-darkness, so this would have been in the winter. My memory tells me I was walking toward DuPont Circle Metro. There was a certain side street that I’d walk through (I was obsessed with patterns at the time, so I regularly took the same path home — as opposed to later, when I became obsessed with entropy and would take extraordinary measures to AVOID patterns — and along this path, there was a certain streetlight that, more often than not, would switch off as I passed underneath it. There were stages of acknowledgement of this phenomenon. First, acknowledgement that a pattern was developing. Then, anticipation. Then, familiarity, and some sort of odd internal pleasure (confirmation bias? validation?) when it occurred. Then, wondering what the phenomenon was. Then the realization that to even bring up the possibility that it could be anything but malfunction and coincidence would lump me in with the crazies. As in, even further than I had already lumped myself in by my strange associations, writings and cultivated friendships.

Looking back, I should have known there was probably a working theory. But back then, information was not as plentiful or easy to come by as it is now. Even I, who collected fringe texts and even ran fringe text-based bulletin board systems (BBSes), had not come across this particular phenomenon discussed in print at the time.

This weekend I decided to look into it further, and discovered that there are texts regarding the phenomena. It’s called Street Lamp Interference, or SLI, and the people who cause it, or to whom it occurs, or who notice it, are called SLIders.

http://mysteriousuniverse.org/2013/05/streetlamp-interference-a-modern-day-paranormal-mystery/

Murder Ballad of the Week, 1/12/15: Omie Wise

One of my favorites, but pretty brutal. Omie is courted by John Lewis, until she becomes pregnant, and he decides he has to kill her. Over 200 years later, and some men still make that fatal decision.

First recorded version in 1927. The murder in question occurred in 1807.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Omie_Wise

Layla and Majnun

(another source references this old, old story as the source for Clapton’s inspiration for the song Layla)

Follow Your Heart: The Story of Layla and Majnun

By J. T. Coker

Layla and Majnun have been characters for Sufi poets, as Krishna was for the poets of India. Majnun means absorption into a thought and Layla means the night of obscurity. The story is from beginning to end a teaching on the path of devotion, the experience of the soul in search of God. — Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan

The story of Layla and Majnun is one of the most popular in the Islamic world, enduring in legends, tales, poems, songs, and epics from the Caucasus to Africa and from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean. Scholars find good reasons to believe that the central character — Qays, nicknamed Majnun (Madman) — lived in northern Arabia in the second half of the seventh century, five hundred years before the poet Nizami. At the behest of the Transcaucasian chieftain Shervanshah, Nizami collected many of the widely dispersed traditional versions and wove them into his great narrative poem.

No one knows the number of translations of Nizami’s work in the many languages encompassed by Islamic religious culture, but at least forty Persian and thirteen Turkish versions are known, and one scholar states that there are actually over a hundred versions in those two languages alone. An English translation appeared in 1836 which relied on an incomplete text with later additions by lesser poets (this text was used by Eric Clapton in the late 1970s for certain lyrics on his recording Layla and Other Love Songs). The translation by Dr. Rudolf Gelpke [The Story of Layla and Majnun by Nizami, trans. and ed. by Dr. Rudolf Gelpke, English version in collaboration with E. Mattin and G. Hill, Omega Publications, New Lebanon, NY, 1997; all page references are to this edition] published originally in 1966, offers insights into medieval Arabic culture and mores. Though cast in prose, poetry lovers will catch fulfilling glimpses of Nizami’s poetic and mystic genius. Moreover, the Omega edition includes the work’s final chapter, translated by Zia Inayat Khan and Omid Safi.

The story begins with the Sayyid, a man of wealth, power, and prestige, desiring a son and heir. He importunes Allah, who grants his request. The beauty of his son Qays “grew to perfection. As a ray of light penetrates the water, so the jewel of love shone through the veil of his body.” At the age of ten, Qays goes to school and meets his kismet/fate, Layla. “Does not ‘Layl’ mean ‘night’ in Arabic? And dark as the night was the color of her hair.” Love struck them both; others noticed, tongues wagged, and Qays first tastes bitterness. He refrains from seeing her, but his heart breaks and he begins to slip into melancholy. Layla’s tribe, to protect her (and their) honor, deny her right to see him, and he falls into madness: “A madman he became — but at the same time a poet, the harp of his love and of his pain.”

In time Majnun runs away into the wilderness, becoming unkempt, not knowing good from evil. His father takes him on pilgrimage to Mecca, to seek God’s help in freeing him, but Majnun strikes the Kaaba and cries “none of my days shall ever be free of this pain. Let me love, oh my God, love for love’s sake, and make my love a hundred times as great as it was and is!” He continues to wander “like a drunken lion,” chanting poems of Layla’s beauty and his love. Many come to hear him. Some write down the poems he spontaneously speaks.

Meanwhile, Layla holds their love quietly so none will know

she lived between the water of her tears and the fire of her love, . . .

Yet her lover’s voice reached her. Was he not a poet? No tent curtain was woven so closely as to keep out his poems. Every child from the bazaar was singing his verses; every passer-by was humming one of his love-songs, bringing Layla a message from her beloved, . . . — p. 40

Refusing suitors, she writes answers to his poems and casts them to the wind.

It happened often that someone found one of these little papers, and guessed the hidden meaning, realizing for whom they were intended. Sometimes he would go to Majnun hoping to hear, as a reward, some of the poems which had become so popular. . . .

Thus many a melody passed to and fro between the two nightingales, drunk with their passion. — p. 41

Eventually Layla is married to another, but refuses conjugality. Being in love, her husband accepts her condition of an outward marriage only. Majnun learns of the marriage and of her faithfulness. Neither his father nor his mother, when near death, can induce him to return to his people. Wild animals, loving rather than fearing him, congregate in his presence, protecting him. One night Majnun prays to Allah, thanking Him for making him the pure soul he now is and asking God’s grace. He sleeps, and in his dream a miraculous tree springs from the desert, from which a bird drops a magic jewel onto his head, like a diadem.

An old man, Zayd, helps Layla and Majnun to exchange letters and finally to meet, though she cannot approach him closer than ten paces. Majnun spontaneously recites love poetry to her, and at dawn they go their separate ways. Nizami asks:

For how long then do you want to deceive yourself? For how long will you refuse to see yourself as you are and as you will be? Each grain of sand takes its own length and breadth as the measure of the world; yet, beside a mountain range it is as nothing. You yourself are the grain of sand; you are your own prisoner. Break your cage, break free from yourself, free from humanity; learn that what you thought was real is not so in reality. Follow Nizami: burn but your own treasure, like a candle — then the world, your sovereign, will become your slave. — p. 148

After the death of Layla’s husband, she openly mourns her love for Majnun, and dies shortly thereafter. Majnun hears of her death and, mad with grief, repeatedly visits her tomb. He dies and is buried beside his beloved.

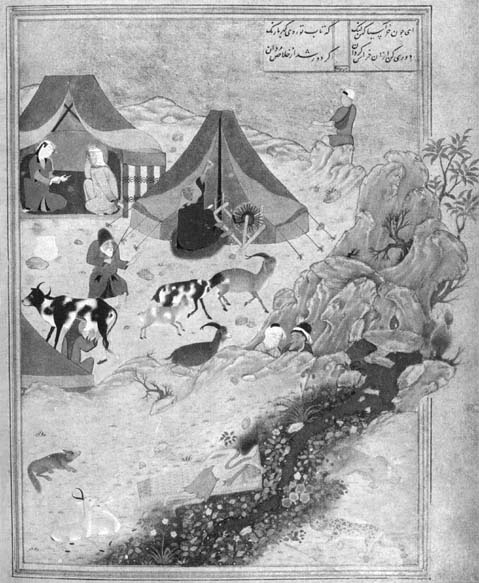

“Majnun Dies on Layla’s Tomb,” Bihzad (c. 1495)

In a dream, Zayd, who tends their joint grave, has a vision of them in paradise, where an ancient soul tells him:

These two friends are one, eternal companions. He is Majnun, the king of the world in right action. And she is Layla, the moon among idols in compassion. In the world, like unpierced rubies they treasured their fidelity affectionately, but found no rest and could not attain their heart’s desire. Here they suffer grief no more. So it will be until eternity. Whoever endures suffering and forebears in that world will be joyous and exalted in this world. — p. 176

On waking Zayd realized that

Whoever would find a place in that world must tread on the lusts of this world. This world is dust and is perishable. That world is pure and eternal. . . . Commit yourself to love’s sanctuary and at once find freedom from your ego. Fly in love as an arrow towards its target. Love loosens the knots of being, love is liberation from the vortex of egotism. In love, every cup of sorrow which bites into the soul gives it new life. Many a draft bitter as poison has become in love delicious. . . . However agonizing the experience, if it is for love it is well. — pp. 176-7

So ends Nizami’s poetic narrative of the story of Layla and Majnun, but to really appreciate and understand this work, it needs to be read, and savored, in full. Is their story a medieval soap opera of epic proportions? It is, if that’s what your heart hears. Is it a cautionary tale inculcating acceptance of earthly injustice and suffering in the Islamic faithful, who will be rewarded in the great by-and-by? It will surely serve, if that’s your concern. Is Majnun “Man” and Layla “Soul,” suffering because denied union while bounded by flesh? Yes, if your concern, your love, leads you to hear it that way. Is it an allegorical Sufi text, instructing seekers in practical means for awakening to the supernal reality of their true, spiritual nature? Only our hearts know for sure — Nizami bids us follow them.

17,318 Days on Earth

Tonight, Eve and I finally got around to watching Nick Cave’s film, 20,000 Days on Earth, released in the US in September, which, as you can imagine, marks his 20,000th day, in a sort of creative fashion, involving psychoanalysis, car rides with people that may not have actually been there, assembling pieces of his history for his museum of Important Shit, and mostly the creative process by which the 2013 album Push the Sky Away was created and recorded.

Highlights: Warren Ellis telling him that a particular phrase sounded like Lionel Richie; and a scene near the end where he’s watching Scarface with his kids.

I followed up the film by making Eve watch the official videos released for the two Murder Ballads duets back in 1995: Where the Wild Roses Grow, with Kylie Minogue, and Henry Lee, with PJ Harvey. I started showing her the Dylan version (Love, Henry from World Gone Wrong) and the Dick Justice version (1929, and included in Harry smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music in 1952), but she was too sleepy to hear any more.

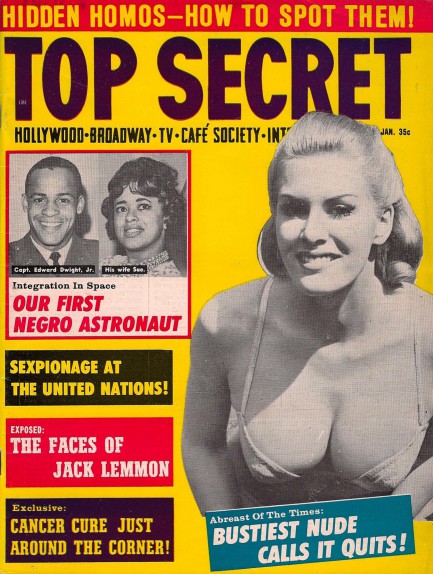

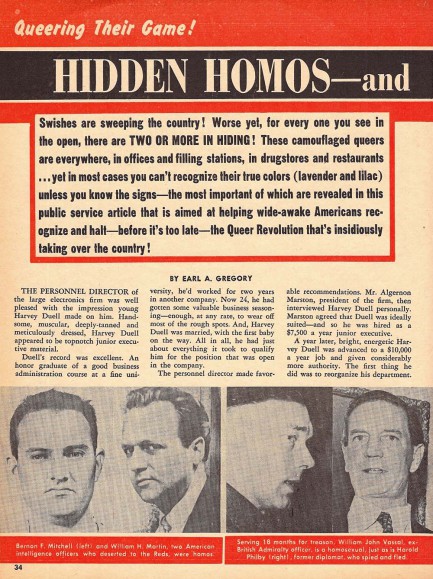

Tabloid views of male homosexuality circa 1964…

If you ever wondered how male homosexuality was thought of in 1964, at least by tabloid publications (was that an accurate representation of mainstream America, I wonder?), wonder no more.

Source: http://www.pulpinternational.com/pulp/entry/Cover-and-scans-from-Top-Secret-published-January-1964.html

Layla Cries

I got bogged down in some Illuminati conspiracy web content earlier today. I spent a significant amount of time reading about Debra Hunter Pitts, aka Layla Cries, who (according to the literature) was the girlfriend of both Eric Clapton and Carlos Santana back in the day, and seems to have love children by both of them.

The story goes that she was taken as a child and trafficked into the covert world of the rich and powerful, due to her psychic abilities. [Note to self – do NOT publish article about my own psychic abilities] After years of horrible slavery and forced prostitution, she was finally rescued, and planned to make it her mission to bring down the power structure. Somehow she met Clapton and Santana (this almost sounds like a TV Funhouse episode so far) and both wanted to marry her, but she didn’t want to marry either. However, she did want to have their children.

Clapton supposedly paid to put her album out in 1971 (Layla Cries – Dressed in Love). In addition, despite what everyone knows about Pattie Boyd being first George Harrison’s wife and then Eric Clapton’s, and being the true inspiration of the song Layla, according to the literature (and an interview with Debra) not only was she the inspiration, she actually wrote the song and gave it to Clapton, originally titled Baby.

I have thus far been unable to confirm the existence of the Layla Cries album. It sounds like a real collector’s item.

Until such a time as I can get my hands on a copy (even a digital copy), this will have to do: The Beatles performing the Dead Kennedys’ California Uber Alles.

Is Everyone a Murderer?

A friend posted an excellent article yesterday, To Fall In Love With Anyone, Do This. The article is excellent, and so is the article linked from it, No. 37: Big Wedding or Small, which contains the 36 questions used in the scientific experiment which led to a couple of strangers falling in love in a lab.

But that’s not really what I’m sharing today. The mere title of that article reminded me of the title of an Okkervil River album, Don’t Fall In Love With Everyone You See, a cautionary title if I’ve ever heard one. There’s no title track per se, that you could play on repeat on your iPod Nano to keep you reminded not to fall into that trap, but there are some real gems on the album. It was released in January 2002, just a few months after 9/11.

But that’s not really what I’m sharing today. The mere title of that article reminded me of the title of an Okkervil River album, Don’t Fall In Love With Everyone You See, a cautionary title if I’ve ever heard one. There’s no title track per se, that you could play on repeat on your iPod Nano to keep you reminded not to fall into that trap, but there are some real gems on the album. It was released in January 2002, just a few months after 9/11.

The album is home to one of my favorite modern murder ballads, which is what I really wanted to talk about this morning. Westfall, according to Wikipedia, comes from recollections of the Yogurt Shop Murders. I don’t remember reading about this horrible case before, but boy, was it a clusterfuck. Four teenaged girls shot, bound and gagged, then the shop they were in set on fire. And that’s how authorities found them. And somehow over fifty people confessed to the crime. HOW? I don’t care how good a detective you are, how to you get FIFTY PEOPLE to confess to a crime that they obviously did not commit????

Clearly there is more to this still-unsolved mystery.

Long-awaited results on female squirting…

As usual, the headline is at least a slight distortion of the study, not the last word. The gist of the article is that they have proven that the bladder fills and empties during these events, but there are chemicals in the fluid that aren’t in pre-sex urine. So I would call that a mixed verdict. The next step, according to the article, is to find out why these things happen.

http://www.iflscience.com/health-and-medicine/women-squirting-during-sex-may-actually-be-peeing

This man is your god.

This man is your god.